In response to the article The genetic origins of the Indo-Europeans, recently published in Nature, Jenny Larsson was one of the researchers interviewed by the popular science magazine Forskning & Framsteg. The text, Den Indoeuropeiska språkgåtan kan vara löst, based on the interviews, is available to the subscribers (in Swedish).

Genetic researchers have cracked a classic archaeological and linguistic mystery – where did the Indo-Europeans come from?

Archaeologists and linguistic historians have been searching for the cradle of the Indo-European languages for almost 250 years. When archaeologists found thousands of clay tablets with an unknown language, Hittite, in 1906, they had to tear up their theories about the language group’s early development. The Anatolian languages are the extinct branch of the Indo-European language tree to which Hittite belongs. Researchers behind two new studies published in Nature previously suggested that Anatolian arose in the Caucasus, east of the Black Sea. But this did not fit well with the models of linguistic historians. Now they are instead placing the origin between the Don and Dnieper rivers in Ukraine and Russia. “We knew that the Anatolian language group had branched off much earlier than the others, but we thought that it originated in the steppe. When the 2022 article came out, many linguists were quite dissatisfied. We saw no linguistic connection to the Caucasus, where, for example, horses are missing, which is found in Hittite and which we can reconstruct back to the original language. And so their dating was far too early. But now it fits quite well with our ideas”, says Jenny Larsson, professor of Baltic languages at Stockholm University, research leader of the interdisciplinary project Lamp on ancient languages and culture, and the co-leader of the Center for the Human Past.

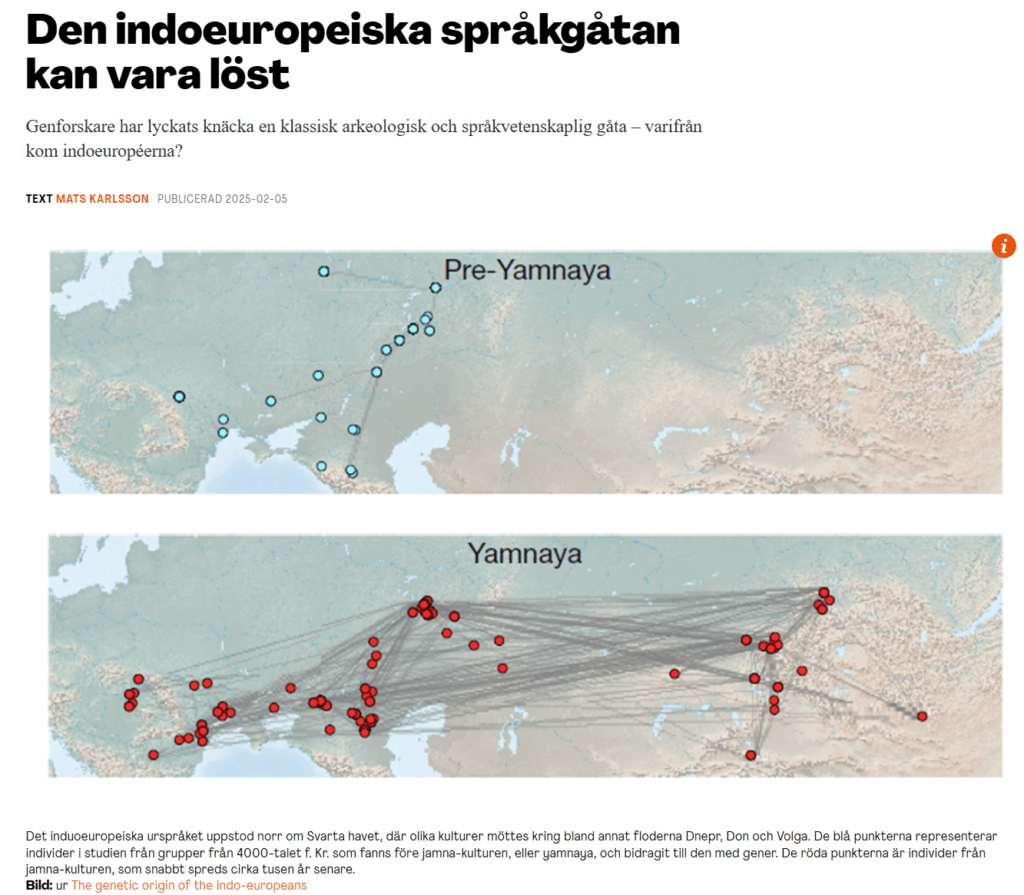

The steppe north of the Black Sea was a crossroads for several groups that mixed and spread in different directions, in several rounds. Around 4300 BC, the so-called Proto-Indo-European split into at least two groups: the Anatolian, which spread eastward, and the Core Indo-European, which spread northward, according to the new studies.

From the northern group, the cattle-herding culture Jamna culture, or Yamnaya, was formed. A thousand years later, it suddenly – and very quickly – spread over a 500-kilometer wide area from west to east. In central Europe, the group mixed with early farmers into what archaeologists call the Corded Ware cultural complex. The branch of this that reached the Nordic region is called the Battle Axe or Boat Axe culture.

Genetics confirmed the picture in a way that archaeology could not. According to archaeologist Anders Kaliff, professor at Uppsala University and one of the researchers in the Lamp project, it has been difficult to see this in the archaeological material, as very little bone material has been found from the Anatolian range.